State of Misinformation 2021— Europe

The internet has a problem, and it’s a rather deceptive problem that everyone seems to be aware of, but no one seems to notice. Even though the internet is where we conduct business, do our research, catch up with friends, and conduct nearly every part of our lives, it’s filled with intentionally misleading information. The internet certainly wasn’t created with checks and balances to affirm the validity of the content posted, but it seems at this point, trust and accountability would’ve gotten better.

But in fact, it’s worse.

Fake news — misleading headlines, news stories, images, and videos intentionally created to provide false information — are not only appearing to maliciously deceive, but are typically created to go viral, spreading misleading information faster than it can be corrected. And for many, the problem is they don’t know it’s a lie, and end up believing whatever version of reality the creator intended.

Simply knowing that fake news is out there has increased mistrust around certain websites and social media platforms, and has even caused people to question any news they consume in any medium. Now, fake news has created such a suspicion that even credible news sites are being questioned more than ever before.

Is there anything that can be done about fake news, or should we just accept that all media is tainted at this point? Or has is the fake news problem finally returned us to the root of the issue: The internet needs a way to validate and authenticate true, fact-based content, and flag the fake news for what it is.

Methodology

This report examines the encounters people have with fake news and misleading content on the internet, how it’s impacted their behaviors and decisions, and how much of a threat they believe fake news to be to society.

A similar study has been conducted by us also in the United States and one specifically in the Netherlands. These reports can also be requested.

On December 10, 2020, we surveyed 1000 people living in Europe to get their assessment of the fake news problem — and to get their thoughts on how to solve it.

Key Findings

We found a number of key findings around where people go to for news, how big of a threat fake news is, and how they believe it can be solved.

Our respondents believed they could spot fake news when they saw it — yet they still shared it. 93% were confident they could recognize it, yet many still mistaken shared pieces of fake news. This means that they’re still seeing a lot of fake content they believe is real — which is the intent.

They believe they only see it a few times per week. 65.6% of respondents believed they only encounter fake news up to five times per week on social media and search engines — only upwards of one post per day. Yet how many fake posts a day go by unnoticed?

Fake news is causing more people to check facts and sources. 34.6% now check facts and sources more as a result of fake news, and 56.1% will attempt to verify misleading information when they see it.

They mostly encountered fake information and authentic material used in the wrong context the most. They also encountered manipulated content, imposter news sites, fake news sites, and parody content.

Yet fake news isn’t considered a wide-spread threat to European society. Even though misleading information did impact personal decisions on a small scale, and national elections on a large scale, respondents still saw it as much less of a threat than terrorism, data theft, or climate change.

Increasing transparency can solve the fake news problem. While respondents were split on who was responsible for solving the problem and how, they agreed that increasing insight into authorship, sources, and changes over time would increase trust. Over 50% of the respondents think that messages without a clear sender should not simply go viral tomorrow via search engines or social media platforms. Over 64% also think that changes made to messages on the internet should be transparent to the user.

The problem can be solved but will require government intervention. 37% of respondents believe that the problem of fake news on the internet can be solved. 51% of respondents believe that the government and regulators will need to get involved in order to see the problem addressed.

Criminalization of fake news. 66% of respondents said they would support regulations that made it a crime for people and organizations to knowingly create and share fake information.

Part 1: Profile of Who We Surveyed

Where we get our news from is always evolving, but the last few decades have shown a shift away from more traditional forms of news sources like print newspapers and radio, to more digital or visually-based sources. With anyone having the ability to post whatever they like online — whether they’re affiliated with an organization or not — those wishing to post intentionally misleading material have no deterrent from doing so. We asked our respondents if they knowingly came across fake news, or if it was misleading them too.

Who we surveyed

1000 participants we surveyed represented the UK and Europe, and came from all different stages of life. They ranged in age from 16 to over 54, with the majority being between 18 and 24 (28.1%). The gender split was more female (55.2%). Our participants also had varying income levels, represented various industries, and had various education levels. They also represented 23 different countries, the top five being the UK (41.2%), Italy (13.1%), Spain (7.9%), Greece (6.2%), and Romania (5.1%).

Where people get their news from has shifted in the past 12 months

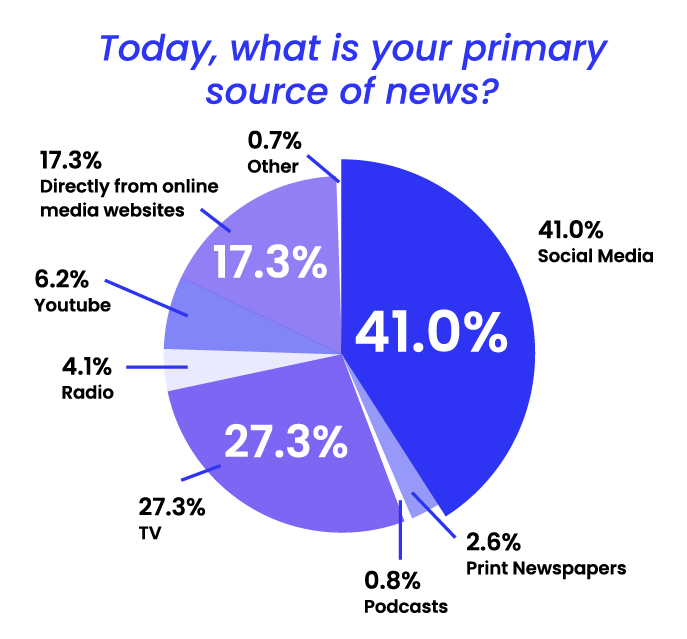

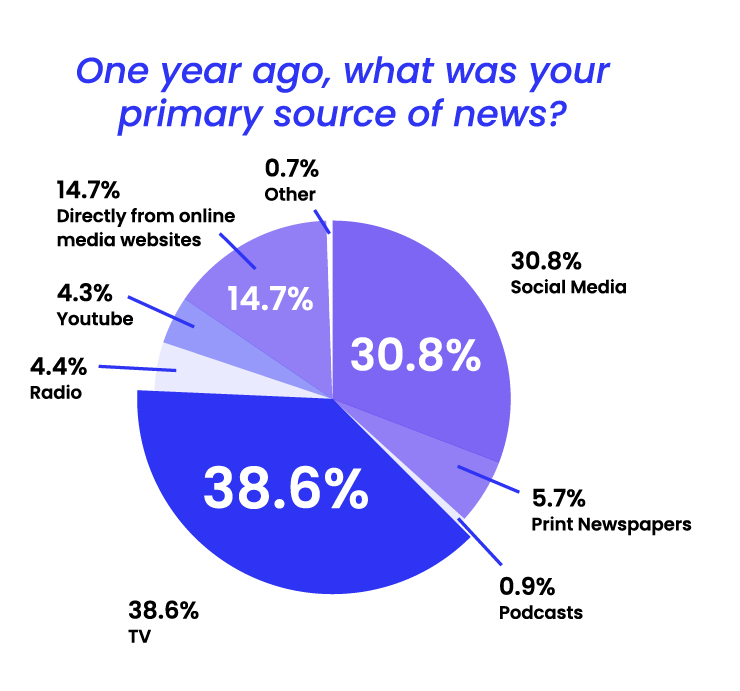

Where were you getting your news last year, and is it different this year? We found that the two primary sources of news traded spots. TV was the primary source last year for 38.6% of our respondents, with social media second for 30.8% of them. This year, social media took the lead by a lot, going up by 10.2% for a total of 41% of our respondents, with TV dropping by 11.3%. This could be due to growing usage and confidence in social media over television sources.

Getting news directly from an online media source’s website also rose this year by 2.6%, possibly showing that respondents wanted to check the validity of the content, or that they frequent their preferred trusted websites.

Other sources that shifted include print newspapers going down from last year (5.7% to 2.6%), podcasts staying about the same (.9% to .8%), radio reducing slightly (4.4% to 4.1%), and YouTube increasing (4.3% to 6.2%).

They are (over)confident they can spot fake news

Did our respondents know fake news when they saw it? It seems that fake news might not be much of a problem, because 93% were confident they could spot it: 33% were very confident, and 60% were somewhat confident. The remaining 7% were not confident at all.

But if fake news is created to deliberately look like a piece of factual content, would they necessarily be able to recognize it? This seems to be the biggest issue: People are confident they know what it looks like, yet fake news is still out there.

But they have also personally shared fake news by mistake

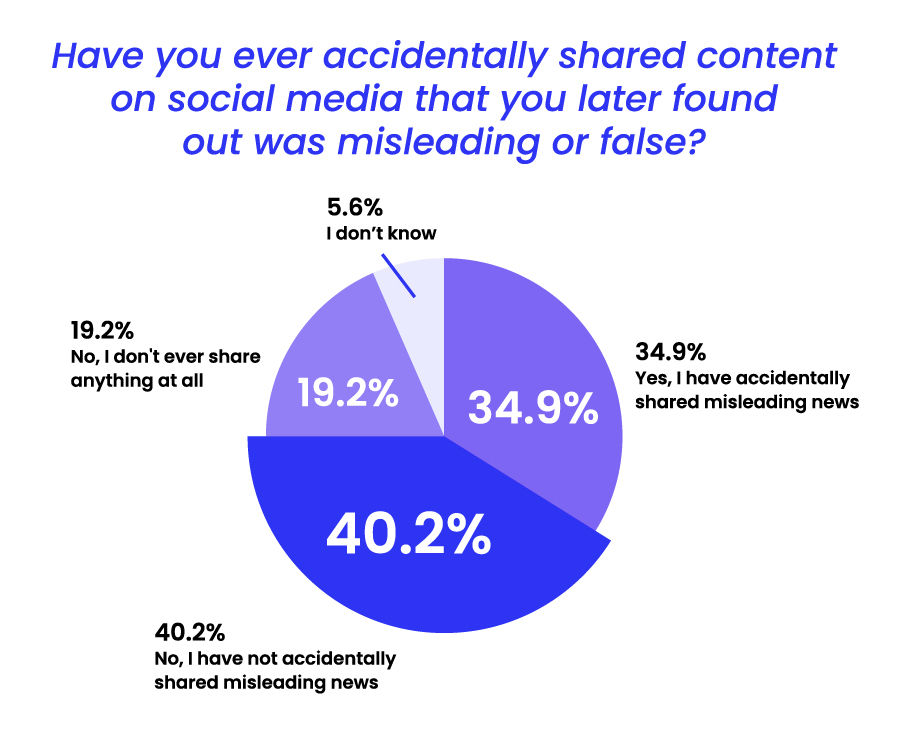

Despite being confident they could spot it, 34.9% admitted to sharing fake news by accident. 40.2% were certain they had not shared fake news at all, while 19.2% hedged themselves against sharing misleading content by choosing not to share anything.

34.9% of our respondents mistakenly sharing fake news means that they actually couldn’t spot it before they shared it, and found out afterwards that it was false. This seems to undermine the 93% of respondents above who were confident they could spot fake news when they saw it. And for those who responded that they’ve never shared fake news before, how can they be so sure?

Summary

Our respondents now turn to social media as their preferred source of news, yet trust themselves to be able to pick out fake news when they see it. But our responses show that they’re perhaps a little too confident in their ability to spot fake news, because many of them have mistakenly shared fake news themselves. This simply speaks to how misleading content can easily deceive the viewer.

Part 2: Encounters with Fake News and Misinformation

If fake news is indeed out there, where is it? And is there one place on the internet where it shows up more than others? We wanted to find out about our respondents’ experiences with encountering fake news, and what kinds they’ve seen, based on the six types of fake news according to The Columbia Journalism Review.

Encounters with fake news on social media

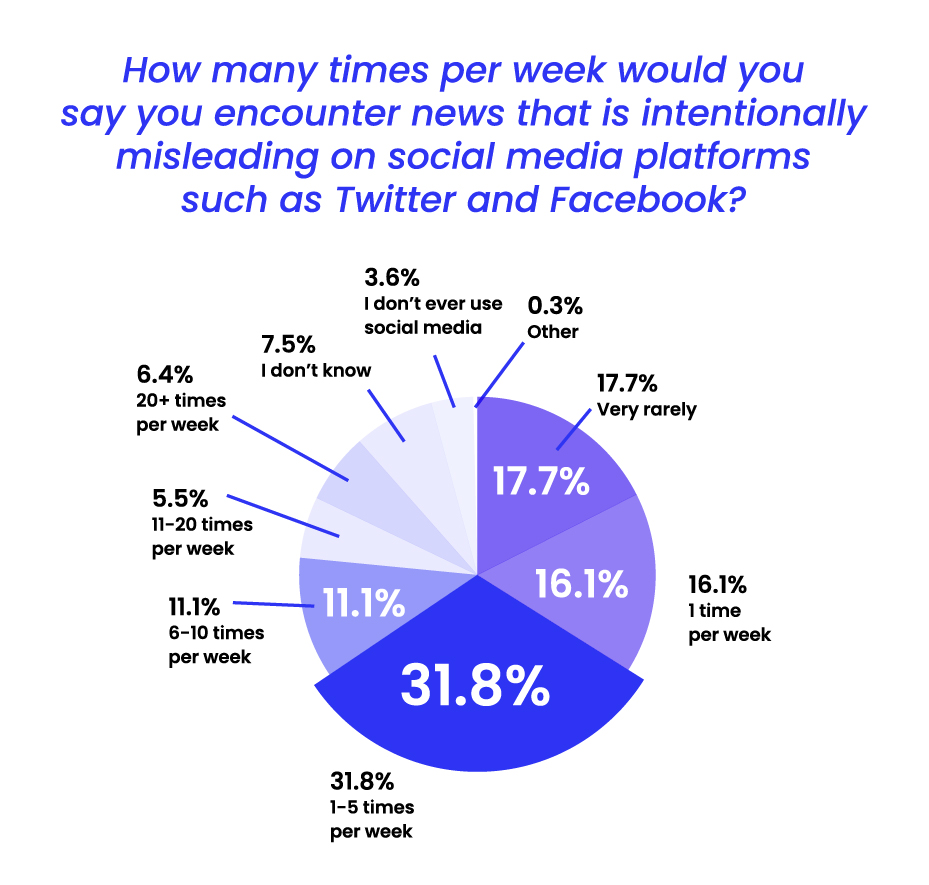

What misleading information do our respondents see on social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter? Or were they seeing any? The majority of our respondents believed that they were only seeing fake news one to five times per week (31.8%) on social media — which is seeing at most one post a day. The next largest group (17.7%) believed they very rarely saw any fake news. In total, 65.6% of respondents believed they only encountered fake news up to five times per week.

A much smaller percentage (23%) believed they encountered misinformation over six times per week, up to over 20 times per week. 7.5% didn’t know if they saw misleading news or not on social media.

Encounters with fake news on search engines

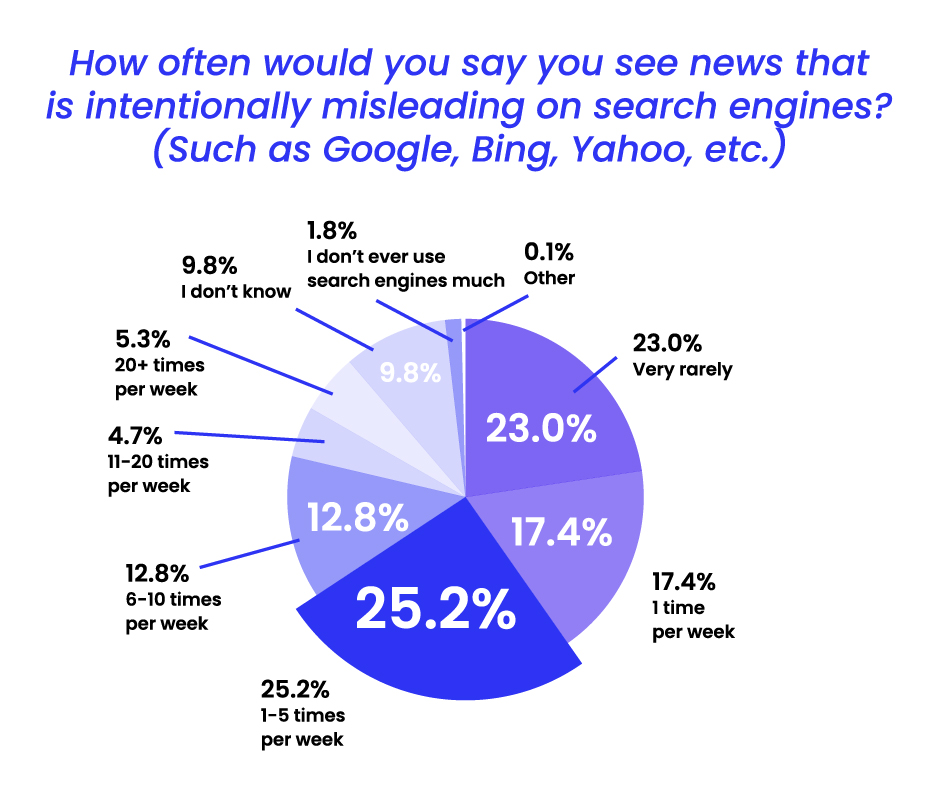

What was the frequency at which our respondents were seeing fake news appear on search engines like Google, Bing, and Yahoo? Less than social media, it appears. 23% of respondents — 5.3% more than social media — believed they very rarely encounter fake news through search engines. But it was actually the same percentage of respondents (65.6%) as social media who believed they only encountered fake news up to five times per week.

About the same amount as above (22.8%) believed they encountered misleading news six to over 20 times per week, and 9.8% didn’t know if they saw anything misleading on search engines, a bit higher than on social media.

Despite the top three choices remaining the same as social media, our respondents here were more confident they saw fake news rarely or once per week on search engines. That confidence in search engines is likely due to the fact that they can see where their content is coming from, as opposed to a social media post. In fact, later on we’ll see that this is a way respondents want to increase trust in online content.

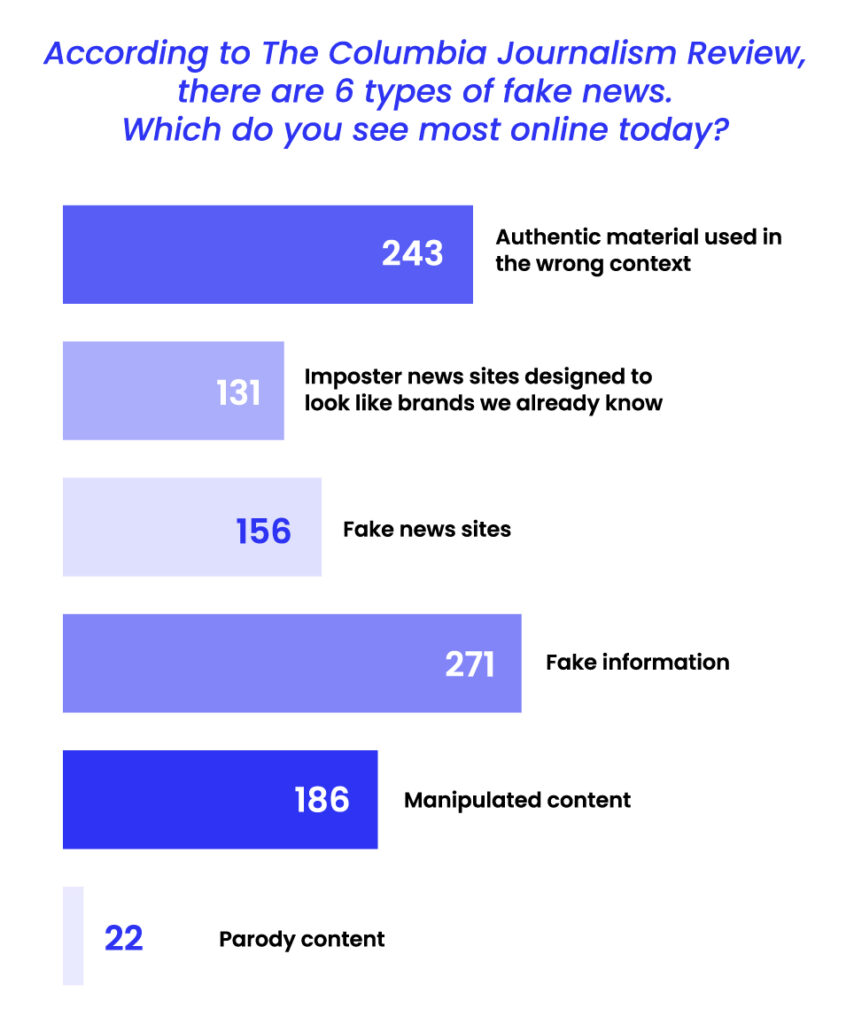

The six types of fake news people may encounter

According to The Columbia Journalism Review, there are six types of fake news: authentic material used in the wrong context, imposter news sites designed to look like brands we already know, fake news sites, fake information, manipulated content, and parody content. We wanted to know which of these our respondents had seen the most online.

For them, it was fake information the most (26.9%), usually meant to disparage someone or undermine confidence in something. A close second in terms of content were authentic material used in the wrong context (24.1%), which are videos or photos from another event or time that are said to be from today to provide false context. Respondents also encountered manipulated content (18.4%), fake news sites (15.5%), and imposter news sites designed to look like brands we already know (13%), with parody content the least encountered (2.2%).

Summary

In terms of finding fake news on the internet, our respondents were more confident they’d see less of it on search engines, but felt that they were seeing about the same amount — one to five posts per week — on both search engines and social media. And while our respondents were able to point out which kind of misleading content they saw online, from fake information to doctored images and videos, were they indeed able to pinpoint every piece of misleading content that came their way?

Part 3: Trust on the Internet

Fake news is essentially pieces of content that are untrustworthy. So what information or sites can be trusted on the internet, and how do those sources stack up against one another? We wanted to know if there are any sites on the internet that can be trusted, what they are, and what if anything do they have in common.

Trusting websites with professionals behind them

What types of websites did our respondents find trustworthy, or that they felt the content and information on the sites was accurate, researched, and truthful? It’s no surprise that sites with trained professionals or authorities behind them ranked highest. Our respondents rated government websites first (46%), followed by medical websites like hospitals and pharmacies (45.8%), legal websites (36.1%), and financial websites like banks and investment firms (29.9%).

What ranked the lowest in terms of trust? The rest of the internet ranked lower than the more professional site above, with 13.2% of respondents. And only 12.4% of respondents thought ecommerce sites were highly trustworthy, perhaps due to mistrust around sales pitches, or the lack of vetting ecommerce sites go through.

Who to trust to provide accurate news

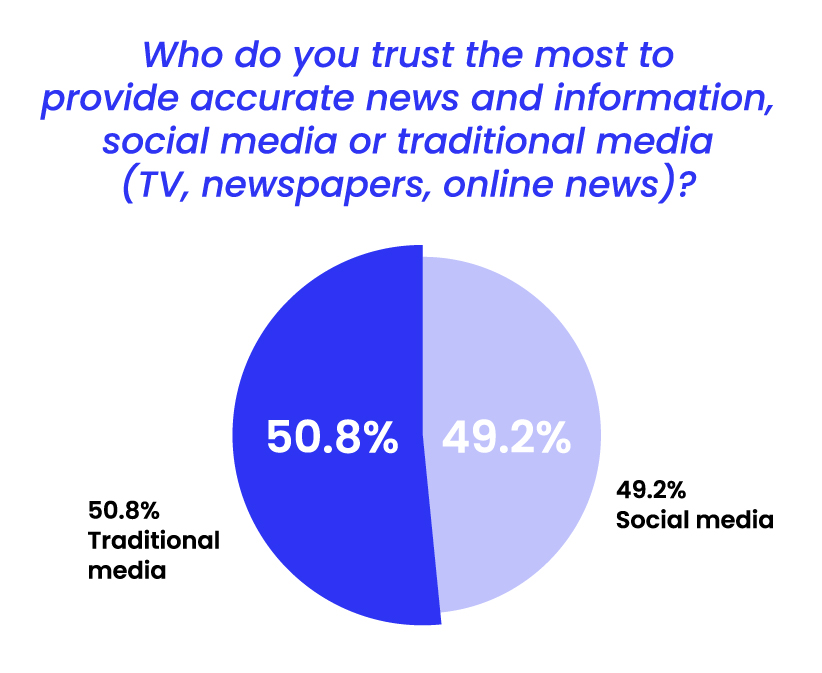

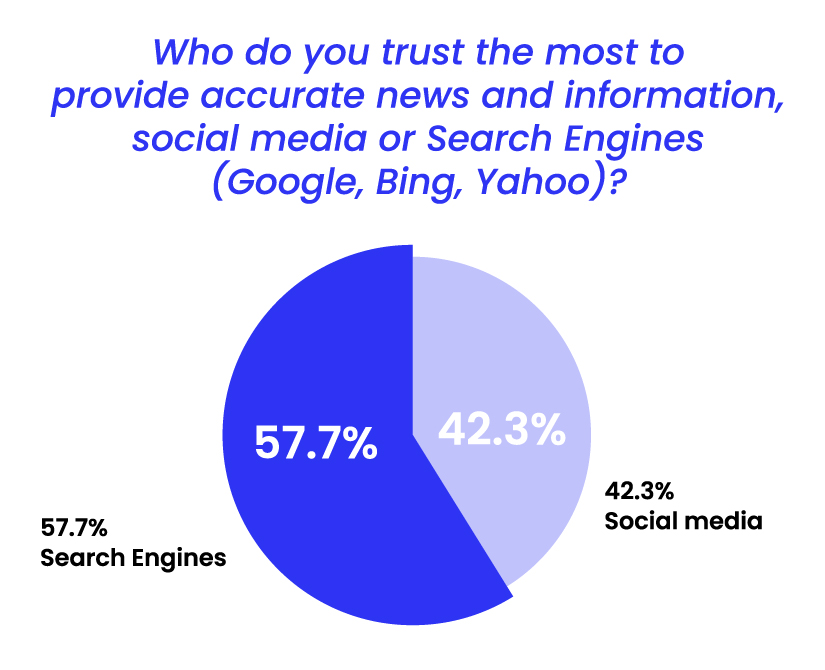

We already know that our respondents tend to turn to social media the most for their news. But we want to find out more about what kinds of sources they trusted through some one-to-one comparisons.

First, our respondents felt national news (56.5%) would provide more accurate news and information than local news (43.5%).

Our respondents also found near equal confidence in traditional media (50.8%) — like TV, newspapers, and online news sites — and in social media (49.2%).

As we saw above, respondents trust search engines (57.7%) to provide them more reliable information than they do social media (42.3%).

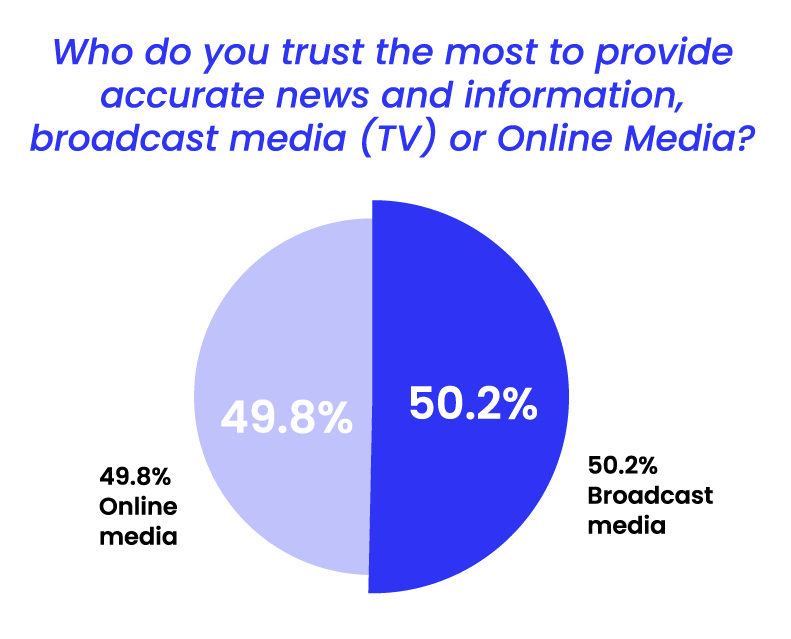

Respondents also found both broadcast TV media (50.2%) and online media (49.8%) could be counted on nearly equally.

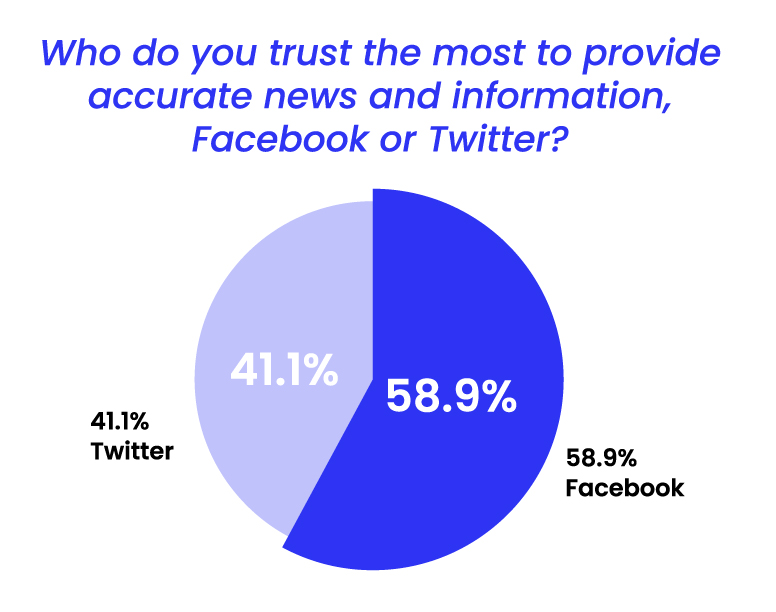

Our respondents also felt that Facebook (58.9%) provided more accurate news and information than Twitter (41.1%).

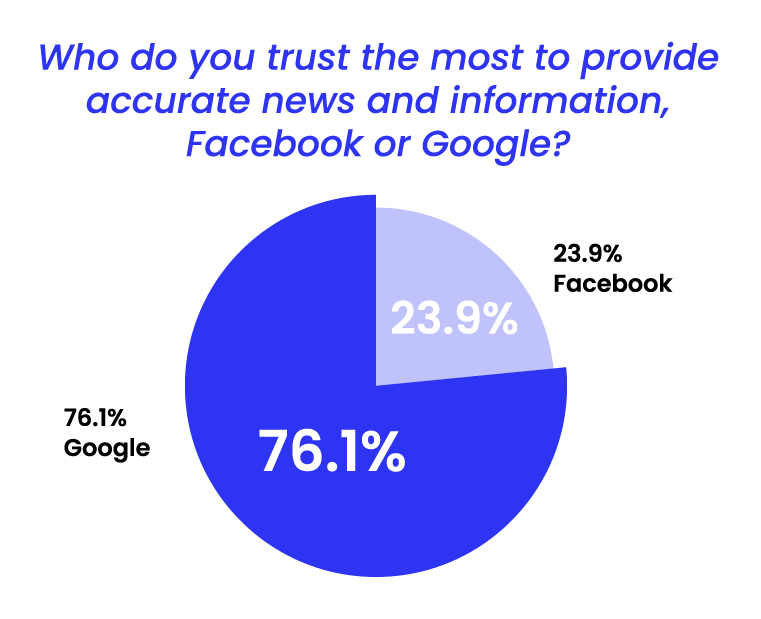

But Facebook (23.9%) was no comparison to Google in terms of providing accurate information (76.1%).

Which social media they trust the most

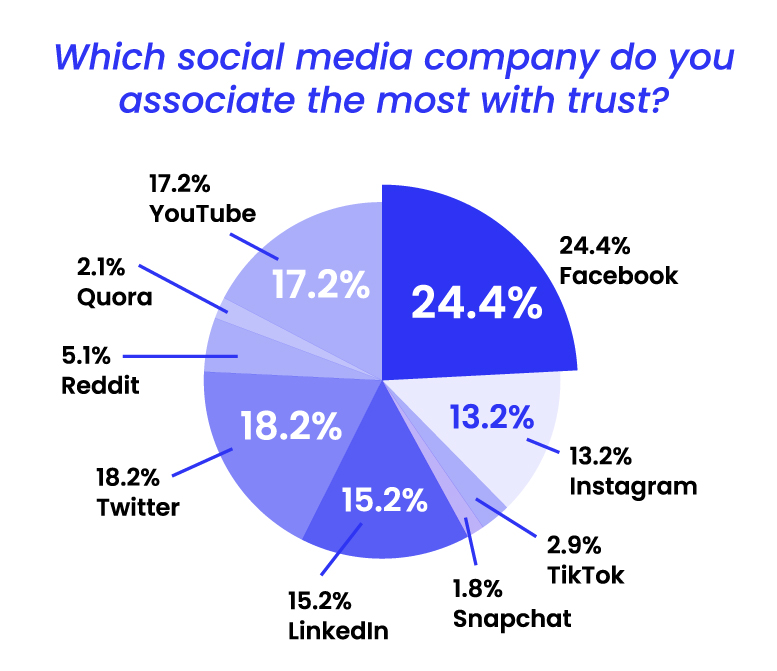

In knowing that our respondents turn to social media for their news, and that they value social media as a trustworthy source just as much as traditional media, we were curious what platforms they had the most confidence in.

The most trusted platform was Facebook at 24.4% (which also ended up being the most distrusted platform, too). Considering Facebook has the largest worldwide reach, it’s become a home of social conversation and news sharing, so it would make sense that our respondents had confidence in its validity.

Twitter came in second at 18.2%, which this past year became a hub for social initiatives and activism worldwide, and a viable source of news on the pandemic.

LinkedIn was the third most trusted platform at 15.2%. As a platform focused on networking and professional advancement, with current and potential employers looking at posts, it makes sense that a professional site would be held to higher standards of trust and transparency.

Which social media they trust the least

Facebook, the highest trusted platform, also placed as the highest distrusted platform, with 37% of respondents saying they lacked confidence in it. Despite a small number marking Facebook as both their most and least trusted platform, this shows a polarized respondent pool viewing the same site through very different eyes. It begs the question of whether those who use Facebook deem it trustworthy, and those who don’t use it just have the opinion that it’s not, based on what they hear in the media. Or is it the other way around?

We found the same situation with Twitter, which placed as the second most trusted platform, and third least trusted platform at 10.9%. Twitter showing up at opposite ends of the trust spectrum also shows a polarization in respondents either based on usage or opinion, or both.

The second least trusted social media platform was TikTok, at 20.6% of our respondents. The Gen Z micro-video platform came under scrutiny this year regarding its security. So are the respondents users who find it untrustworthy, or non-users basing an opinion on what they heard?

Summary

With our questions regarding what sites could be trusted or were found to have solid, reliable content, we were able to see a sliding scale: government sites were the most trusted, sites focused on professional services were right behind, and ecommerce sites and the general internet came in as lowest trusted. But we didn’t find a sliding scale at all when we asked about trusted social media platforms, and found almost a circle: Sites that were rated both reliable and unreliable, sources of reliable news some of our respondents were confident in, and sources of fake news others respondents wouldn’t go near. It makes us ask whether trust here is being based on experience or opinion?

Part 4: Impact of Fake News

If we know that fake news is out there, and if it can be spotted, then it must not be a threat or affect us in any way. That wasn’t the case with our respondents, who found their behavior and decisions impacted by fake news. They also believe that misleading information has the potential to do harm to society if unchecked.

The personal impact of fake news on behavior

How has fake news had an impact on our respondents? 33.2% believed it didn’t have any impact at all on them personally, which also assumes they’re not being affected by undetected fake news. However, the largest portion of our respondents (34.6%) were impacted to take action, and said that fake news causes them to check facts more thoroughly themselves to verify the content as truthful.

However, about an equal amount of respondents chose to either stop going to a specific outlet (12.4%), reduce the amount of news consumed overall (11.4%), or reduce the amount of time spent on social media (8%). In other words, instead of verifying the content, they decided to disengage with it, or avoid the site it was on. It’s certainly an option, but one that will leave the fake news unverified.

The personal impact of fake news on decisions

We also wanted to know if fake news had any impact on their decision-making. Like above, a fair amount replied that no, the content had no effect on their decisions (45.8%). But for 34.9% who said yes, misleading information found online actually did have an impact on their decisions. A good portion of our respondents also replied that they weren’t sure if it had an impact — which means it could have, they just didn’t know it.

Responding to distrusted information

We saw above that one of the impacts of fake news is that respondents check facts more closely. We wanted to know what our respondents would do when encountering misleading information on a website. 56.1% of them would do the same as above: Seek out additional information from other sources to verify or check the content. Similar to above, though, were the other half of respondents who either accepted the suspect information, or disengaged: 16.9% delayed their actions or decisions, 14.7% continued through the site but felt anxious about it, and 8.9% simply continued without regard for it. Only a small percentage (2.6%) hedged the risk by changing their identity.

How big of a risk is fake news

So far our respondents are encountering and recognizing fake news in their everyday travels on the internet, and we’ve seen that it does have an impact on decisions and behaviors. But how big does the impact go? Do our respondents believe that fake news is a threat to society?

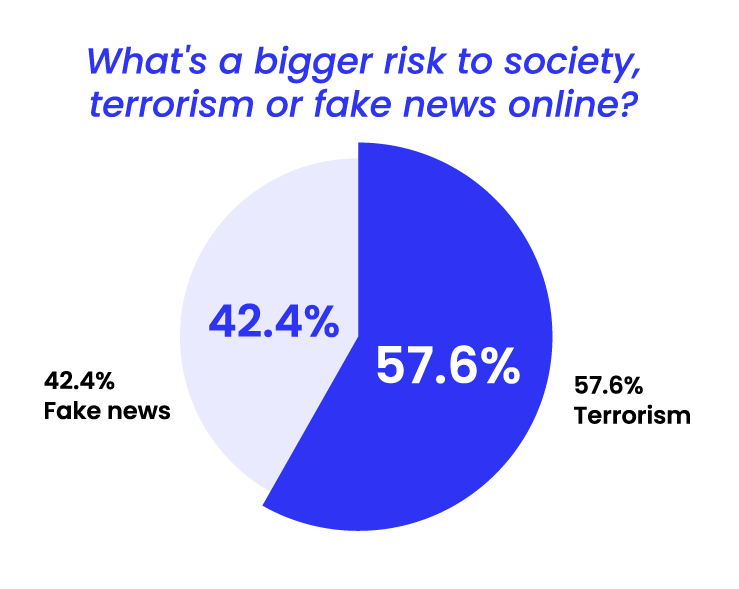

Not really. Our respondents believe that there are much greater threats to society than fake news, like terrorism (57.6%)…

…data theft (63%)…

…and especially climate change (75.2%).

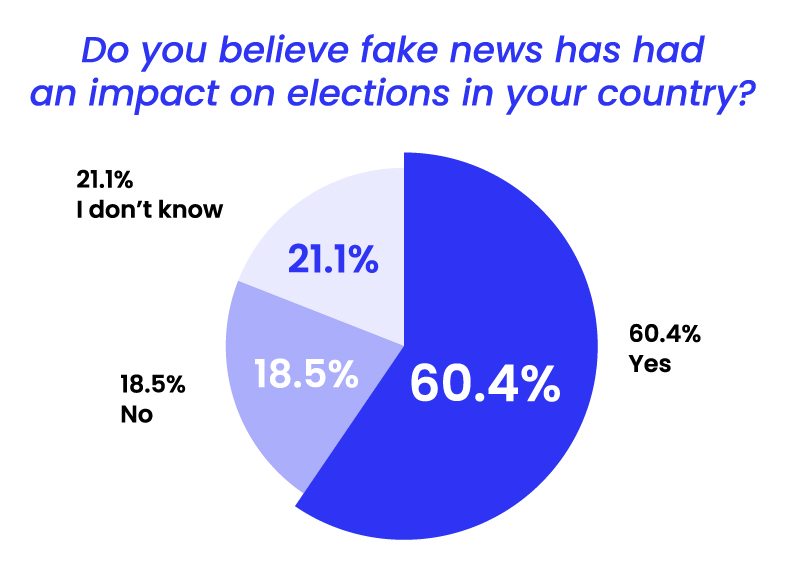

Fake new impacts elections — massively

While fake news may not be as big of a threat as terrorism, data theft, or climate change, our respondents still saw it playing a remarkable role in elections in their countries. 60.4% believed that some kind of misleading information or content impacted elections, which would have been in upwards of 23 different countries.

This means that fake news like the six mentioned above — authentic material used in the wrong context, imposter news sites designed to look like brands we already know, fake news sites, fake information, manipulated content, and parody content — influenced voters who impacted the future of a country.

18.5% believed fake news did not have an impact in their country, but a higher number (21.2%) didn’t know if it did.

Summary

Fake news actually does have an impact on behavior, and has caused many of our respondents to begin verifying content for themselves when encountering misleading information. But that’s typically only half. The other half either disengages with the platform the fake news is on, continues on knowing about the misleading information, or turns off social media altogether. It seems that one approach is actively trying to solve the problem and educate themselves, and the other might be ignoring it.

When it comes to the threat fake news poses to society, our respondents felt it was significant, but that it couldn’t compare to the severity of other threats like terrorism, data theft, and climate change.

Throughout this survey, we’ve been seeing a notable level of “I don’t know” responses to some of the questions, which could signal confusion around identifying fake news and its impacts, or uncertainty over how to respond to it.

Part 5: Solving the Fake News Problem

If fake news is maliciously created and intended to be misleading, believable to the extent that people are mistakenly sharing it, and if it’s causing people not to trust the websites and social media platforms for fear that they may encounter it, then something should be done to eliminate it. But what? We asked our respondents what they felt could be done to solve the fake news problem.

Solving the fake news problem — but how?

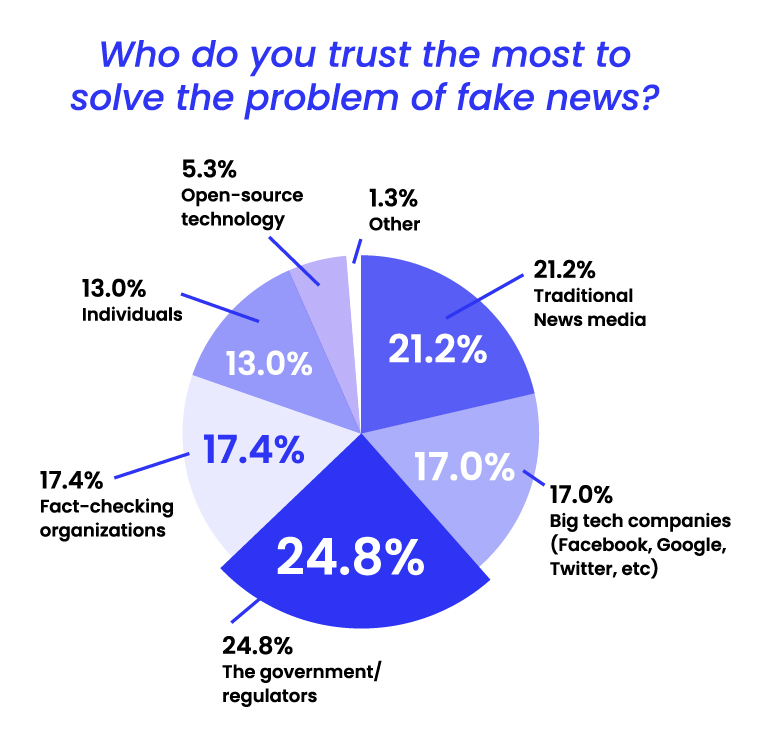

How do we solve the fake news problem — or rather, who should solve it? Our respondents were fairly split over the answers. The top answer was that it was up to the government and regulators (24.8%) to solve the problem of fake news infiltrating the media, with 21.2% saying that it was up to traditional news media to counteract the flood of fake news out there.

Nearly tied were fact-checking companies (17.4%) who would serve as independent third parties, and tech companies like Facebook, Google, and Twitter (17%) who would need to clean up their own platforms. 13% believed that it was up to individuals to solve the problem, and 5.3% thought open-source technology could help. Finally, the responses in “Other” served to capture those who believed that no one could solve the fake news problem.

Is fake news anyone’s fault

Since we asked who could solve the problem of fake news, we wanted to know if our respondents held anyone specifically accountable for the issue. Our respondents were split over who was responsible. Or, rather, everyone was responsible in nearly equal ways: Tech companies like Facebook, Google, and Twitter for allowing it (34.4%), individuals for posting it (26.1%), news media for not checking it (22.2%), and government and regulators for not stopping it (17.3%).

Should it be media or the government

Considering that fake news is inherently a media issue, but since respondents believed that the government should have a large role to play in solving the problem of fake news, we asked if the government should intervene. Half of our respondents (50.6%) agreed that they should, with 36.6% believing that media and tech companies should be able to solve it without government intervention. 12.8% weren’t sure which approach would be the right solution.

Is anyone addressing the problem of fake news in an effective way

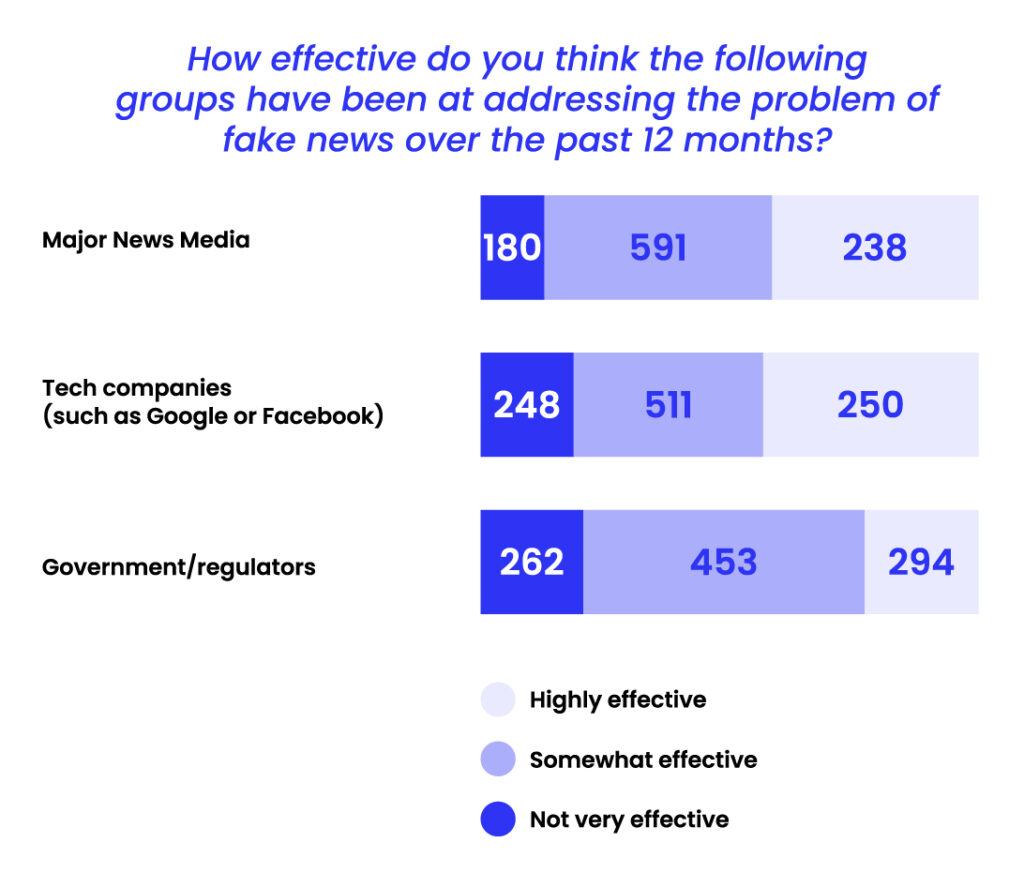

Our respondents continued with their high level of confidence in government being able to mitigate the risks of fake news by edging out government and regulators as being the most highly effective when it came to addressing issues of fake news over the past year. However, major news media were more effective overall at addressing issues than government or tech companies.

Should fake news be a crime

Due to the potentially harmful and wide-reaching impacts of fake news, we wanted to know if they would support regulations that made it a crime for people and organizations to knowingly create and share fake news. Overwhelmingly our respondents replied that they would (65.6%). 16.7% replied that they would not support regulation (perhaps keeping in mind various freedom of speech laws, and who would ultimately define “fake news”), and a large 17.6% weren’t sure either way.

Solutions to Fake News: Increasing Trust Online

Instead of government regulations and intervention, we wanted to know how the internet could become more trustworthy, and what were some methods that could be employed by content creators and websites to increase overall transparency and accountability?

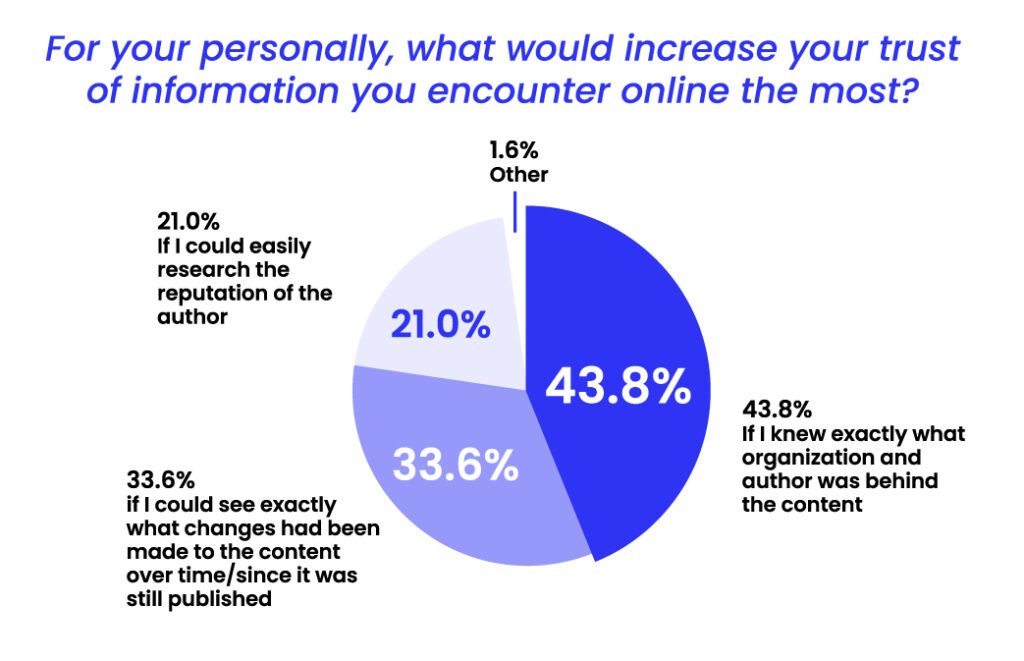

Our respondents believed that if they knew exactly what organization and author was behind the content (43.8%), they would trust it more. Another way they would trust the content more is if they could see exactly what changes had been made to the content over time (33.6%). Still another way was if they could easily research the reputation of the author (21%). In other words, if a reader or viewer could get transparency around who created the content and how it was changed, that would make the content more reliable.

Solutions to Fake News: Impact on Trust

In digging further, was there one of these solutions that increased their trust the most? All of the approaches would seem to help, but being able to know more about authorship edged out as having the most impact on trust, second to knowing who was behind the piece of content.

Solutions to Fake News: Trusting Unaffiliated Content

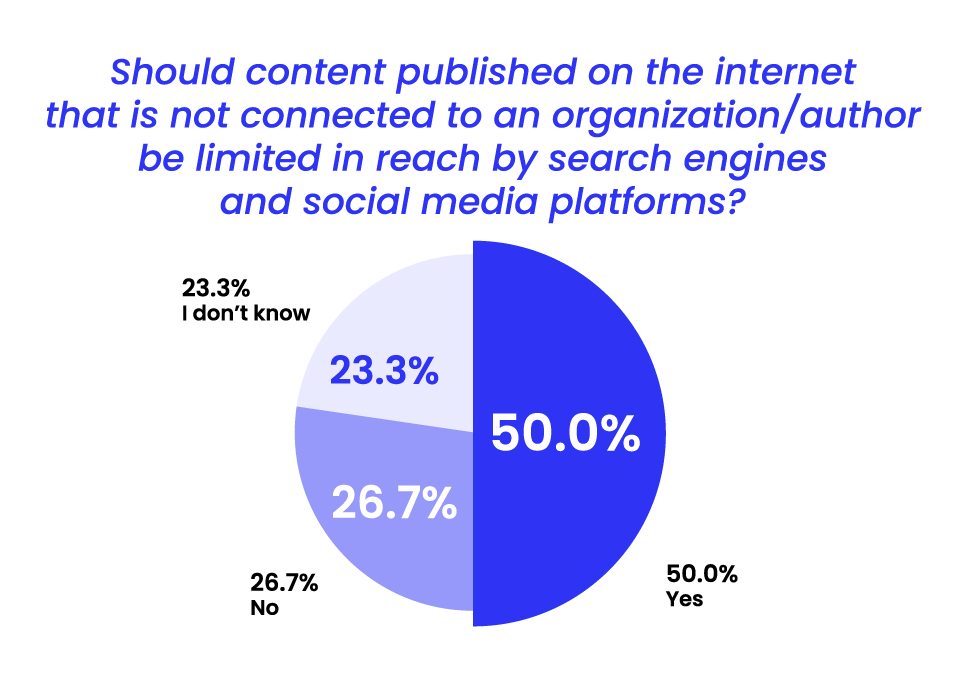

Considering that our respondents valued authorship and being able to know exactly which organization and creator was behind a piece of content, we wanted to know if they felt that search engines and social media platforms should limit content that wasn’t connected to any organization or author. Exactly half agreed that they should. 26.7% disagreed, not supporting an effort to limit unaffiliated content, with 23.3% not knowing either way.

Solutions to Fake News: Trusting Required Documentation of Changes

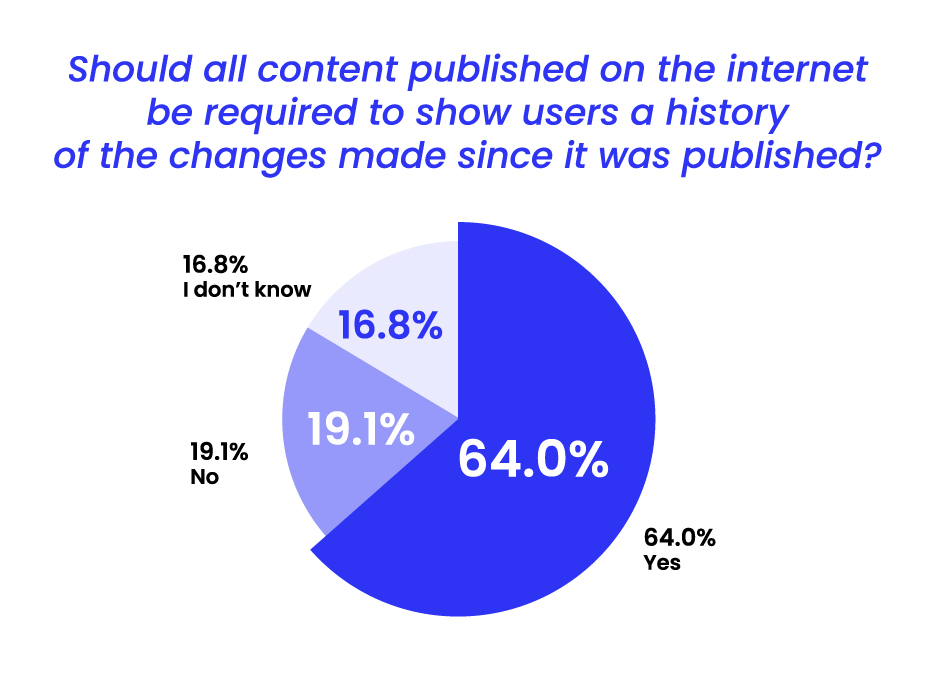

Since our respondents also replied that they’d trust content more if they could view a record of changes made to it since it was created. We wanted to know if they thought that every piece of content published online should hold to that standard. 64% said that yes, that should be required of all content. 19.1% said no, and 16.8% weren’t sure either way.

Summary

According to our respondents, everyone had a hand in creating the problem of fake news — and now everyone needs to have a hand in solving it. What is the way to begin to decrease fake news and misleading content on the internet, and increase trust in what we see and read? Our respondents believed that the solution was in more transparency around authorship, and being able to see into who created the content originally.

Again, we saw a high response rate of “I don’t know,” meaning that there’s either question around the right thing to do to solve the problem of fake news, or there’s confusion around what appropriate regulations and standards should be implemented.

Part 6: Outlook For the Future

After coming this far, and after learning so much about how our respondents were impacted by fake news, how much of a risk they feel it is, and how they thought about solving it, we finally wanted to know definitively if they thought this problem was solvable — or is fake news here to stay?

Solving the fake news problem — can it be done?

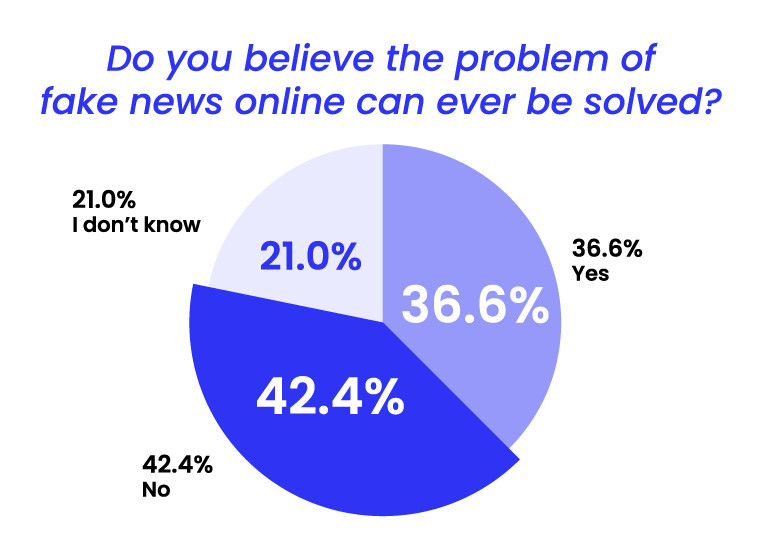

Unfortunately, our respondents were more negative about the solution to fake news, with 42.4% believing that it’s an unsolvable problem that’s here to stay. 36.6%, however, were more positive, believing that it can be fixed and that fake news could become a thing of the past. A full 21% didn’t know either way if it could be solved.

Will fake news continue to be an issue

But fake news is here to stay, at least for the time being. 34% believed that the problem would remain the same, while 32% believed it would only get worse. Only 23.6% believed there would be an improvement and a decrease in the frequency and impact of fake news. 10.4% didn’t know what the future held for more trustworthy news content.

Conclusion

While our respondents were split on what the future of fake news will be, we do know that the right path forward is to see a decrease in any kind of misleading, deceptive, or luring misinformation on the internet, meant to disparage, trick someone over to one side of thinking, or simply cause chaos.

Fake news is a solvable problem. But as we saw, too often people run away or just ignore it when they encounter it, instead of trying to either prove it, check it, or call it out.

But some of our respondents knew the way forward, in that the path away from misleading content is through an increase in fact checking and being able to verify content. In other words, fight fake news with transparency and accountability.

As our respondents rightly pointed out, it’s a problem that all entities need to help solve so that someday the internet can be a reliable, transparent, and safe space for anyone creating content and for anyone reading it.